My husband Bob and I have a goal to visit all 50 states, and we are almost there. One of the states neither one of us had been to was Oklahoma, so on a whim we planned a trip for December 2014. We decided to throw in some places in Northern Texas and Western Arkansas to expand the trip.

We flew into the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, picked up a rental car, and headed for Little Rock, Arkansas, a distance of about 300 miles. After a good night's sleep, our first stop was the state capitol building (because we also have a goal to visit all 50 capitol buildings). It was all decked out in its seasonal finery:

The Governor's office (Mike Beebe at the time) had two doors, and both were beautifully adorned. Here's the main entrance:

We love visiting state capitol buildings. They present interesting insights into the history and personality of a state. One of the unique exhibits in the Arkansas Capitol is this African American doll display:

Many of these are versions of the ubiquitous "Kewpie" doll, which first appeared in 1909 in the Ladies' Home Journal.

A placard by the display notes: "In 1914 a black Kewpie was introduced, dubbed the Hottentot. The name was based on the real life Khoikhoi tribe in southern Africa. When European immigrants colonized the area in the late 1600s, they labeled the natives 'Hottentots' in imitation of the sound of the Khoikhoi language. Today, this term is considered derogatory, but in [the artist's] time it was viewed as humorously exotic."

I'm pretty sure the label "Hottentot" is no longer considered humorously exotic.

Another display case contains dolls modeled after more modern figures:

From left to right: Martin Luther King, Jr., Barack and Michelle Obama, and Nelson Mandela:

Two other very important African American figures are included: Michael Jackson and a USPS letter carrier. Was there a time in Arkansas when all the letter carriers were African-Americans?

My favorite exhibit at the state capitol, however, is a completely different kind of display located outside on the capitol grounds. A group of life-sized figures collectively entitled Testament is a tribute to the nine African-American students who had the courage to integrate Little Rock High School in 1957, three full years after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. the Board of Education that state laws establishing separate schools for white and black students were unconstitutional.

We've seen one other civil rights memorial on a state capitol grounds in Atlanta, Georgia, but it was small and not nearly as moving as this one.

The nine students chosen to pioneer public school integration in Little Rock had been carefully selected by the NAACP and the school board based on their excellent grades and school attendance.

Each member of the "Little Rock Nine" is represented by a figure in the memorial.

Located on the north side of the capitol, the figures are looking directly--and symbolically--at the Governor's office window:

A bust of Orval Faubus (Governor from 1955 to 1967), who ordered the Arkansas National Guard to block the students' entrance to the school, still stands in a place of prominence in the capitol.

Not everyone supported Governor Faubus's decision, including the school board, which issued a statement condemning his action. Still, rioting continued outside the school, and the lives of the Little Rock Nine and their families were constantly in danger. A few weeks after that first attempt at integration, President Eisenhower stepped in and sent the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army to escort these brave students to class and to stand guard to ensure their safety. The students attended all year long, in spite of continuous physical and verbal abuse by other students.

Rather than continue with integration, and not liking being ordered around by the federal government, the following year Faubus signed a decree that closed all four public high schools. The schools were not reopened for a full year (a period called "the Lost Year" in Little Rock), and during that time resentment towards the black community grew. When the high schools finally reopened, black students were once again part of the student body, but they suffered great persecution then and for years to come.

I stood in the middle of the group and faced the Capitol, trying to imagine walking in their shoes, but I couldn't begin to envision what those students went through. I don't think I would have had their courage. We spent a long time at this memorial. I felt I was walking among true heroes.

Before our trip to Arkansas, the only things I knew about Little Rock were that Nellie Forbush in the movie South Pacific was from Little Rock (Impressive trivia, isn't it?) and that it had been the site of the first integrated high school. The Little Rock Nine Memorial made me anxious to see the school itself, which is about 1.4 miles from the Capitol. A national historic site with exhibits detailing the important events of 1957 and subsequent years is located just around the corner from still operating Central High School.

It is a small but really worthwhile museum, full of images, videos, and paintings that bring the events of 1957 to life.

It was eerily quiet the afternoon we were there, so we assumed the students were out on winter break:

In 1957, 1,800 students in grades 9-12 attended Central High School. These days there are 2,400 students in grades 10-12. Very little has changed physically in the last 57 years, but I hope there have been significant social changes. Today, the school is about 54% black and 43% white.

We took our pictures from the sidewalk of this dilapidated and boarded-up house, located directly across the street from Central High. If houses could talk, this one would have some stories to tell.

If you are interested in more information about the Little Rock Nine story, this ten-minute video is well-worth your time:

READING:

Of all the books for sale in the excellent gift shop of the Little Rock High School Museum and Visitor Center, this young adult novel was the one that caught my eye. In The Lions of Little Rock, Kristin Levine tells the story of Marlee, a very intelligent but painfully shy girl thirteen year old who makes friends with Liz, the new girl in school. When authorities discover that Liz is a black girl trying to pass as white, she is kicked out of Marlee's school. It's 1958, the year following integration by the Little Rock Nine. It is known as "the Lost Year" because public high schools have been closed by order of Governor Faubus. Tension in town is high. Marlee and Liz face difficult decisions that affect not only themselves, but also their families.

If I were taking an older child to any of the civil rights sites in the South, I would first have him or her read this well-written and thought-provoking book. In addition to telling an important historical story, it explores related topics of friendship and loyalty, how racist attitudes are developed and how they can be changed, and the need for courage in the face of injustice.

It is a great read, even for an adult.

We flew into the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, picked up a rental car, and headed for Little Rock, Arkansas, a distance of about 300 miles. After a good night's sleep, our first stop was the state capitol building (because we also have a goal to visit all 50 capitol buildings). It was all decked out in its seasonal finery:

The Governor's office (Mike Beebe at the time) had two doors, and both were beautifully adorned. Here's the main entrance:

And here's the second. There was a huge Christmas tree beneath the rotunda

The top of the tree, viewable from one of the upper levels, was crowned with a blown glass ornament made by Texas native James Hayes that reminded me of Dale Chihuly's work:

While we were in the building, a steady stream of choruses from local schools sang on the upper balcony of the rotunda, their clear, sweet voices echoing throughout the building. Proud parents and grandparents made up the appreciative audience.

We love visiting state capitol buildings. They present interesting insights into the history and personality of a state. One of the unique exhibits in the Arkansas Capitol is this African American doll display:

Many of these are versions of the ubiquitous "Kewpie" doll, which first appeared in 1909 in the Ladies' Home Journal.

A placard by the display notes: "In 1914 a black Kewpie was introduced, dubbed the Hottentot. The name was based on the real life Khoikhoi tribe in southern Africa. When European immigrants colonized the area in the late 1600s, they labeled the natives 'Hottentots' in imitation of the sound of the Khoikhoi language. Today, this term is considered derogatory, but in [the artist's] time it was viewed as humorously exotic."

I'm pretty sure the label "Hottentot" is no longer considered humorously exotic.

Another display case contains dolls modeled after more modern figures:

From left to right: Martin Luther King, Jr., Barack and Michelle Obama, and Nelson Mandela:

Two other very important African American figures are included: Michael Jackson and a USPS letter carrier. Was there a time in Arkansas when all the letter carriers were African-Americans?

My favorite exhibit at the state capitol, however, is a completely different kind of display located outside on the capitol grounds. A group of life-sized figures collectively entitled Testament is a tribute to the nine African-American students who had the courage to integrate Little Rock High School in 1957, three full years after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. the Board of Education that state laws establishing separate schools for white and black students were unconstitutional.

The nine students chosen to pioneer public school integration in Little Rock had been carefully selected by the NAACP and the school board based on their excellent grades and school attendance.

|

| Photo from here |

A bust of Orval Faubus (Governor from 1955 to 1967), who ordered the Arkansas National Guard to block the students' entrance to the school, still stands in a place of prominence in the capitol.

|

| Photo from here |

Rather than continue with integration, and not liking being ordered around by the federal government, the following year Faubus signed a decree that closed all four public high schools. The schools were not reopened for a full year (a period called "the Lost Year" in Little Rock), and during that time resentment towards the black community grew. When the high schools finally reopened, black students were once again part of the student body, but they suffered great persecution then and for years to come.

I stood in the middle of the group and faced the Capitol, trying to imagine walking in their shoes, but I couldn't begin to envision what those students went through. I don't think I would have had their courage. We spent a long time at this memorial. I felt I was walking among true heroes.

I find it somewhat ironic that this Civil War memorial is just around the corner of the capitol building from the Little Rock Nine Memorial:

Then again, given the military presence at the integration of Central High School, there is a weird appropriateness as well. It was a battle zone in every sense of the word.

Before our trip to Arkansas, the only things I knew about Little Rock were that Nellie Forbush in the movie South Pacific was from Little Rock (Impressive trivia, isn't it?) and that it had been the site of the first integrated high school. The Little Rock Nine Memorial made me anxious to see the school itself, which is about 1.4 miles from the Capitol. A national historic site with exhibits detailing the important events of 1957 and subsequent years is located just around the corner from still operating Central High School.

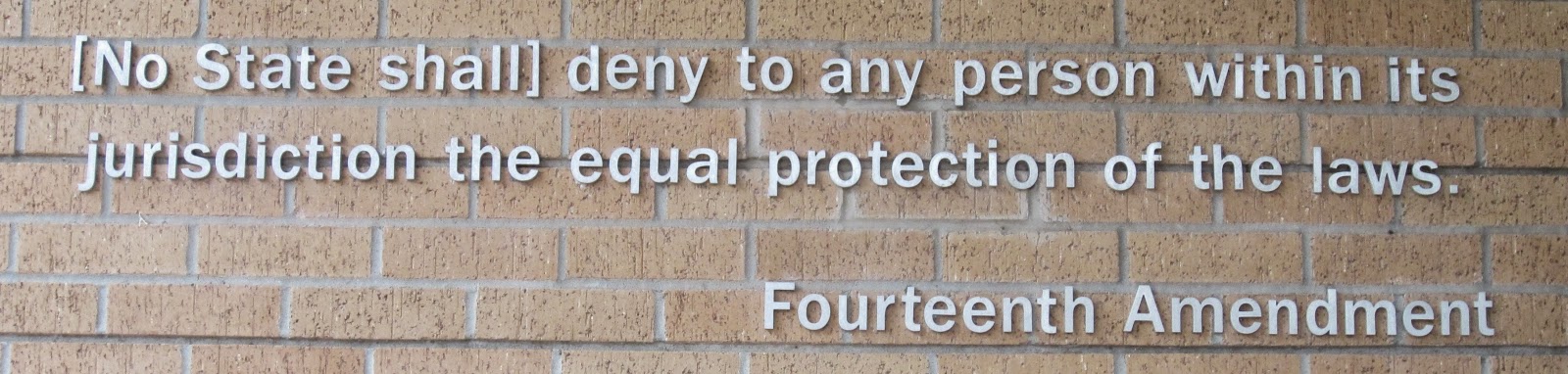

|

| Words on the outside of Little Rock Central High School Museum and Visitor Center |

Poor Elizabeth Eckford somehow missed walking in with the rest of the group and tried to enter the school by herself on the first day. She was only fifteen years old. It is her statue that leads the group at the memorial at the Capitol.

Ernest Green was the only senior among the Little Rock Nine. He made history by being the first African-American to graduate from a previously all-white high school in 1958.

Along with information about the crisis at Central High School, the museum includes some basic background about the Civil Rights Movement.

It was eerily quiet the afternoon we were there, so we assumed the students were out on winter break:

In 1957, 1,800 students in grades 9-12 attended Central High School. These days there are 2,400 students in grades 10-12. Very little has changed physically in the last 57 years, but I hope there have been significant social changes. Today, the school is about 54% black and 43% white.

|

| "Spurred on by the Governor's speech, an angry crowd of about 200 people assembled outside Central High on the first day of school. The size of the crowd doubled the next day." |

If you are interested in more information about the Little Rock Nine story, this ten-minute video is well-worth your time:

Of all the books for sale in the excellent gift shop of the Little Rock High School Museum and Visitor Center, this young adult novel was the one that caught my eye. In The Lions of Little Rock, Kristin Levine tells the story of Marlee, a very intelligent but painfully shy girl thirteen year old who makes friends with Liz, the new girl in school. When authorities discover that Liz is a black girl trying to pass as white, she is kicked out of Marlee's school. It's 1958, the year following integration by the Little Rock Nine. It is known as "the Lost Year" because public high schools have been closed by order of Governor Faubus. Tension in town is high. Marlee and Liz face difficult decisions that affect not only themselves, but also their families.

If I were taking an older child to any of the civil rights sites in the South, I would first have him or her read this well-written and thought-provoking book. In addition to telling an important historical story, it explores related topics of friendship and loyalty, how racist attitudes are developed and how they can be changed, and the need for courage in the face of injustice.

It is a great read, even for an adult.

I was very touched by the courage of the Little Rock 9 and horrified by our society that was so blatantly prejudice. It gives pause to consider ones own prejudices.

ReplyDeleteEven with the current racial problems in our country, it's nearly inconceivable that there was ever a practice (in my lifetime!) of racial separation. Love the Testament memorial. What a stirring tribute.

ReplyDeleteI wonder if one day we will get to the point where race doesn't matter, but it definitely isn't today.

ReplyDelete