Our last stop during the Dunhuang portion of our journey along the Silk Road was the Mogao Caves--also called Mogao Grottoes--another mind-blowing UNESCO World Heritage Site I had never heard of before this trip.

I've decided that western China is ripe for a tourist explosion. They have clearly been working hard to build their infrastructure to support more tourism, and the sites themselves are also being developed to make them more accessible to foreigners, including the use of English descriptions.

Now if they would just add some more western-style toilets. In most of the places we visited in China (aside from our hotels), we had no option but squat toilets. I'm all for experiencing the local culture, but . . .

Okay, okay, back to the caves. Our tour buses left our hotel early (7:30 AM) so that we could beat the crowds, but alas, it was the beginning of an eight-day national holiday in China, and so a lot of the locals had the same plan that we did. After a 30-minute bus ride, we went through a gate, got off the bus, and reboarded a shuttle bus for another 30-minute ride to the caves.

These man-made grottoes house 1,000 years of the largest collection of Buddhist art in the world. There are 735 caves, and so far 492 have been opened and restored to some degree. The caves in the photo below, seen from our shuttle bus, are still in their original state and are not open to tourists:

In 1900, a Buddhist priest and the abbot of the Magao Caves, Wang Yuanlu, discovered a new cave, now called the Library Cave, that had been sealed off in about 1100. It was filled with tens of thousands of manuscripts and relics that had lain in the naturally controlled climate, undisturbed, for 800 years. It is considered to be the world's greatest discovery of ancient Oriental manuscripts.

|

| Photo from here |

As I had never heard of the Mogao Caves, I had also never heard of the Library Cave. Unfortunately, we also didn't get to see it on this visit. Only some of the caves are open on any given day. In this way the treasures within are exposed to a minimum of light and human breath and other forms of contamination. The Library Cave was not part of our tour.

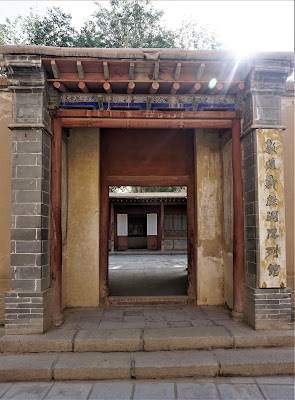

Before we got to the caves, we passed through a well-developed and beautifully landscaped tourist area:

A locked door protects each cave, and only trained tour guides, usually graduate students from the local university, have the key.

If we looked carefully at the upper walls . . .

. . . we might see a hint of what can be found behind the door:

Our excellent guide, a woman who has been studying at the Mogao site for ten years, led us through eight of the grottoes, pointing out features like the Buddhas covering the walls (identifiable by their topknots and the circle--or halo--behind their heads), recurring patterns, and stories in the pictures. It was fascinating.

Example of the repeating Buddhas:

Samples of the entrances to the caves and a view of the terracing:

Conservationists planted poplar trees to make a natural protective barrier for the caves:

These paintings flank the second story door in the photo above:

Look carefully at the wall just under the eaves:

There are little gems everywhere:

. . . including this dragon rain gutter:

A very lucky shot with no people!!

Most the time it looked more like this:

The caves were dimly lit and unfortunately we were forbidden to take photos, even without flash. Here are some pictures from the internet that are more or less representative of the kind of murals we saw:

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

|

| Photo from here |

Pretty incredible, aren't they? Why aren't American and European tourists flocking to this place like they are to the Terracotta Warriors in Xi'an? It is definitely a five-star attraction.

The view from the top level gives a glimpse of the king of all the caves at Mogao. A seven-story pagoda has been built in front of it:

There is a single enormous cave behind this elaborate facade:

While we were waiting for our turn to go inside, we had time to appreciate these water spouts, far scarier than the gargoyles on the Notre Dame Cathedral if you ask me:

Inside this grotto (Cave #96) is a statue of Buddha that was constructed in 695 AD. He is so large, and the vantage point is so close, that even professional photographers can't get a decent picture of him. He is seated, and his hands are resting on his knees. (See enormous hand, upper right.) Even seated, this Buddha is 116 feet tall, the size of an 8-10 story building!

|

| Picture from here |

Someone was filming while we were there. They seemed more focused on the crowds than on the grottoes. Perhaps they are creating promotional materials for the site:

We were given a time to meet up with our full group for a lecture by Michael Wilcox, so we made our way back to the central area next to a few shops. Bob was happy to find some grapes, a fruit this area and the Stans is known for. Although we'd been warned about eating fresh fruit, he ate quite a few with no drastic results to his digestive system.

Michael also covered a few other things, such as the hand symbols in the depictions of the Buddha, as well as our need to be open to good ideas from other faiths. He was his usual passionate, brilliant self, always raising the quality of our experience with his insights.

As he spoke, most of the Chinese people walking by openly stared at us, and as many as a dozen took pictures of our group. One person walked around the tree where we were seated and took a video. Another stopped a took a selfie with a member of our group. Later, on our way to the shuttle bus, a father with four children asked (pantomiming) to take a picture of John, Susan, and me with his kids. We felt like real celebrities. This experience, however, does speak to the lack of western tourism in this area. Clearly a large group of Americans is an uncommon site at the Mogao Caves.

The last thing we did was stop briefly at the Mogao Grotto Museum. The most interesting thing we learned was that in 1921, White Russian soldiers who had retreated from the Bolsheviks into China were temporarily incarcerated in the caves. During their stay, they did more damage to the place than any other group in history. They burned the stairs, walkways, and facades for fuel, painted vulgarities on the walls and statues, gouged out the eyes of the painted Buddhas, and broke off the arms of the statues. Some of that damage has been repaired, but much of it is still visible.

There were some fun artifacts in the museum, and my favorite was this statue with dozens of hands. I think this is Guan Yin, revered by Buddhists as the Goddess of Mercy or Compassion. There have been many days when I wished I had this many hands:

I also enjoyed this display of pigments made from naturally occurring minerals:

Overall, our visit to Dunhuang was a major surprise. Before preparing for this trip, we had never heard of this relatively small (about 190,000, which is small for China) city, but it provided some of the most awe-inspiring and fun experiences of our trip. At 1,500 miles directly west of Beijing and 1,070 miles northwest of Xi'an, it is well off the beaten track and really requires a separate flight to get there. Our next destination, Turpan, was about 500 miles away. In spite of its remote location, I am guessing Dunhuang is going to see a tourism explosion in the coming years.

I've said it before, Dunhuang was probably my favorite place on our trip. The Mogao Caves were just a small part of the reason why. It would be nice to have a better photographic record of what is in the caves. We have so little exposure to Buddhism that it takes longer to process the meaning of it all.

ReplyDelete